So declared my boyfriend, as he watched me play his new computer game Bioshock Infinite (Irrational Games, 2013). I turned around, somewhat dumbstruck. "Why, yes... it has," I replied [NB: some expletive expressions of shock have been edited out of this conversation], "I didn't know you'd been listening to me talk about him."

Confusion ensued, until we realised we had crossed our wires somewhat. He was talking about bloom, the lighting effect used in some video games to mimic the effect of a bright light on vision as experienced through a camera. I was talking about Bloom - Harold Bloom, the [in]famous theorist whose most well-known academic legacy is the always-contentious theory of the 'anxiety of influence' (all poets are influenced by a previous poet, and they're all unhappy about it) and whose best-known extra-academic legacy is his 1994 publication The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages, and with whose works I've been spending an inordinate amount of time lately.

|

| Bioshock Infinite: a potentially Coleridgean vending machine |

When applied to this game, the two ideas are not so disparate as they might at first seem: in fact, one bloom often signals the presence of the other. But it's the theoretical Bloom I want to focus on here. In a lot of ways, this post follows on from my last, in which I read the Romantic sublime into Bethesda's 2011 release Skyrim. It could, in fact have been more closely connected; Bioshock Infinite contains humanoid vending machines which quote from Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and warn you to mind the proverbial albatross - and this is only the most blatant Romantic reference - and a lot of the views could certainly be described as sublime. Connections have already been made between Bioshock Infinite and its hidden literary influences, such as to The Wizard of Oz here. But what about its literary-theoretical ones? In this post, the first of two in which I'll explore this theme, I'm going to look at one of the trailers for the game.

At this point I should say: ***SPOILER ALERT***

|

| Zachary Hale Comstock - from the Bioshock Infinite wiki |

The Bloom connection in Bioshock Infinite is almost as blatant as the Ancient Mariner one; in some ways more so. The main character's names - Booker DeWitt or Comstock depending on which temporal dimension you happen to be in - are loaded with histories:

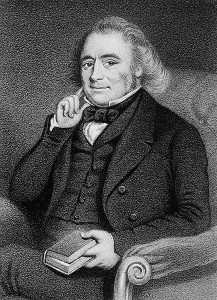

Bryce DeWitt (1923-2004) was a theoretical physicist who, appropriately for Bioshock's needs, advanced Hugh Everett's many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics; Anthony Comstock (1844-1915) was quite literally post-Civil War New York's morality police - George Bernard Shaw coined the term 'comstockery' after one of his plays was censored by Comstock - and the fictional Comstock is something of an Evangelical moralist who consistently reiterates similar morality laws in his floating city of Columbia. Historical influences pervade the narrative, from the anti-abolitionist rhetoric of Columbia's ruling classes to the echoes of the French and Russian Revolutions found in the that of the Vox Populi here. But, as the article linked there suggests, 'Columbia is both the setting and the ultimate threat to be averted at all costs'. And it is in Columbia itself, in the setting, that we can find the most obvious, visual Bloomian tropes. Columbia is a stage: it's a stage on which to talk about influence, historical, literary and, most importantly, familial. |

| The historical Anthony Comstock (source here) |

Now, Bloom's theories, on the surface, are all about the temporal - except that, time and space are not dichotomies for Bloom. Bloomian time and space is more like the Doctor Who timey-wimey-spacey kind - all mixed up. If time changes, so does the space, and spaces affect what goes on in time. And that is what we find in Bioshock Infinite. The historical influences are undeniably important - you need a decent grasp of transatlantic nineteenth century history to follow the nuances of a lot of the plot - and the game is supremely self-conscious about it. This isn't a game which is anxious about its influences, as such; on the contrary, it flaunts them.

The mocumentary trailers released before the game introduce several strands of influence that will remain present throughout the game; the title - Truth from Legend: A Modern Day Icarus? - suggests the elision between historical fact and game, between 'fact' and legend in the narrative itself, and the classical/literary references which underpin so much of the game's plot and imagery - most importantly, Biblical allusions. The documentary itself is reminscent of that cheap 1980s kind 90s kids got shown in school: scratchy prodution company music; the deep, serious voice of a neutral-accented narrator; unsteady graphics. It's an audiovisual scrapbook of the 'history' of the floating city, Columbia, from it's beginning in 1893 to its cessation from the United States following a diplomatic crisis (in China - you're right to think of the later Manchurian crisis) in 1901. The narrator asserts that this city - the star exhibit at the Great Exhibition-esque 1893 World Columbian Exhibition, 'a gathering of the greatest technological feats the world had ever seen' - was the result of the vision of 'one man'. But the narrator is clearly wrong, as his own name suggests: the city arises as the monstrous result of a collaboration between characters within the game, and with the game's developers and diverse social, cultural and historical sources outside of it.

The fact that our narrator's name is A. Bloom surely cannot be coincidence. The unusual spelling of his first name suggests that this is something we should be paying attention to. Firstly, Alistar is introduced after the viewer has been drawn back through a galaxy of stars; the cosmic/legendary/scientific tensions explored in the game are already evident here. Secondly, the name invokes allusions to another contemporary game: Alistar is a Minotaur in League of Legends, the online multiplayer role playing game launched in October 2009. According to his Wiki page, Alistar the Minotaur was 'initially unwilling to cater to his celebrity status as a champion' until he 'discovered that there is power in fame, and he has become a vocal advocate for those whom the Noxian government treads upon'. This emphasis on vocality is important here; both Alistars are, in different ways, oral advocators of truth in the face of something hidden. The Bioshock Infinite trailer narrator's surname reinforces that the viewer - and the future player of the yet-to-be-released game - should be paying close attention to the game's external references, whether they be extra-textual (I'm including literature, film and game here), theoretical, or historical.

|

| A screenshot of the opening of the Bioshock Infinite 'documentary' |